(Translated from Spanish)

Published in Arquitectónica Num. 9, año 5. México: Universidad Iberoamericana-Licenciatura en Arquitectura, 2006 and www.dondeestanloscables.com.mx November 5, 2006

Of his whole career as an architect, José Hanhausen (1918-2005) will be remembered in the history of XXth century Mexican Architecture for being one of the young architects who contributed to the project of the campus for the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM) in Pedregal de San Angel, México City in 1952. He designed the building for the Economy and Law Faculties[1].

Even though religious architecture attracted him, he was able to do very few projects, where he practiced the basic principles of functionalism, such as making shape follow function and achieving a sound harmony between light and space, using material that were common and durable, yet non expensive. He avoided imposing his own personal ideas to his clients, managing to interpret their desires in the most beautiful and functional way. He thrived to create a harmonic space where every aspect would highlight the purpose of it made for prayer and meditation. Has to be recalled that circumstances made ephemeral most of his religious buildings.

In the fifties he built a chapel for the rural town of Zoquiapan, Estado de México, and the all- purpose space for auditorium and chapel at Merici Academy in Cuajimalpa, Mexico City. In the sixties he projected and built the domestic chapel for a nunnery in Condesa, Mexico City, but because of the reorganizing project that built a highway –the Patriotismo Ave.- cutting through that neighborhood, the convent was demolished just a few years after the chapel was consecrated. In the seventies he reconditioned a private residence in the upscale neighborhood of Chapultepec Heights, Mexico City to build a meditation chapel for Misión Alpes. At the turn of the century the house was sold and the chapel was demolished. The reconstruction made of a severely damaged church in Colonia Roma, close to downtown Mexico City after the 1985 earthquake is the only one survivor of his religious architecture projects.

José Hanhausen was also a professor in the Architecture Faculty of the National University of Mexico. He devoted more than 30 years to teach several generations of Mexican and Latin American architects in subjects as project composition, Art History and History of Architecture. He was also a gifted draughtsman and that activity, pursued with a virtuoso technique of watercolor on paper, was his sole distraction in the last years of his life, long time after he had abandoned the practice of building and projecting. His first paintings were made at the end of the thirties, when he started his studies to become an architect. He had the gift of endowing with life his drawings, using well disposed lines and value shadowing, showing none of the lack of spontaneity of those obsessed with artificial perfection. His colleague and fellow school mate in the Architecture Faculty, Arq. Ernesto Gómez Gallardo, referred that once when they were both working in the architectural firm of Arq. Del Moral, he had turned in a careless quick perspective sketch for a project just before leaving for a vacation. When he returned, he found his perspective different: it looked finished and more attractive, full of life, were his words. He was told that Arq. Del Moral had asked young José Hanhausen to fix it up[2].

In 1959 Hanhausen made the illustrations for a book of religious poetry of a Jesuit friend, Angel Martínez Baigorri SJ (1899-1971). He was born in Navarra, Spain, but ended up living and working in Nicaragua and becoming at his death one of Nicaragua most famous literary talents. Hanhausen made some dozen drawings on Fabriano paper, rendered with robust brushstrokes of black ink, applied with a coarse rounded brush, of those used at the time for applying shoe polish. The themes of those drawings, intended for sacred poetry dealt with Christ and History of Salvation, from Creation to Resurrection with few concessions to figurative language, preferring abstraction.

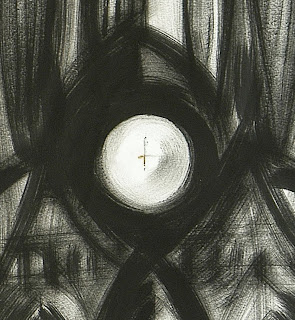

Two of them, the ones that will be analyzed here are different. Those are the only architectonic drawings, depicting imaginary cathedrals. The first one is a Gothic façade and the second one is the interpreted floor plan of the Bramante's 1506 Basilica of San Peter in Rome.

Fig. 2 José Hanhausen. Catedral floor plan. 1959 Sketch. Ink on paper Col. M. Hanhausen, México

Cathedrals as a subject of art are common in Western history of Paint. They can be found from the Middle Ages well into our days. From the Flemish church interiors of the XVth century where the Virgin and the Child smile to their worshippers to the impressionist facades of Rouen Cathedral painted by the impressionist Claude Monet, enfolded in the different shades of light as the hours of day go by, the temple as a symbol of the community who congregates to worship is not new. Auguste Rodin symbolized it with a couple of right hands that get close but barely touch, the "I" and the "You", the "We", closing into a pointed arch, showing that humans are the prime material for building the temple and that effective prayer is at least something that should be attempted by two[3]. José Hanhausen was a fervent catholic and in his mind these temples signified the most important architectonic projects of Western world. The challenge presented to him here was: how to render in paper such a mystery?

Gothic was considered by the revivalist movement in the second half of XIXth century as the style who conveyed the most pure Christian spirituality. Hanhausen felt attracted by that historical period of Western Culture, even though his point of view towards it was strongly romantic. He considered with reverence and nostalgia the far gone time when the community gathered and together built the most beautiful House for God, acting like one man and one soul. That attitude was for him the supreme aim of any architectural endeavors.His ideas on Gothic were the historicist XIXth views of Violet le Duc and Fulcanelli. But he had an experience added to it: when traveling in Europe in the fifties he visited several Gothic Cathedrals, but it was Chartres shrine in Northeast France his favorite. He understood what Gothic was about while enfolded by the blue light of the stained glass of Our Lady of the Beautiful Window. From his trip to Europe he brought in the retina and in his body the measurements of those floor plans, paced by. Proportion was for him first a body sensation, not a mathematical figure, mere measurable corroboration and possibility for a realistic budget at the time of calculating the actual building.

In the second drawing, God's presence is rendered as a central triangle, resulting from converging lines of the precise symmetry of Bramante´s floor plan. God appears to man though his work, when it has been done to please Him. The floor plan resembles the map of Celestial Jerusalem, as a Jungian temennos where the Divine Presence dwells.

Is a key to their reading the concept of the "Dead Cities", as understood in the last half of the XIXth century[4]? At the time whether as a theme for paint or for literature, the cityscape of medieval neighborhoods of quickly developing industrial cities, such as Barcelona and Bruges were very much alluring. These enclaves of time past were regarded as "dead" thus considered attractive topics in the last part of the XIXth century. The triptych of the "Gothic Quarter of Barcelona" painted by Francisco Goitia, and the illustrations of "Bruges, la mort" by Lucién Levy-Dhurmer, the mysterious secluded gardens of German Gedovius and the sacred forests of Charles Marié Du Lac[5] are good examples of such idealized places for the confused man at the turn of the century, who considered progress and all the changes it brought to his world with uneasy ambivalence.

But Hanhausen´s drawings have to be read from a different perspective. Although quoting Gothic and Renaissance, he is not attempting an archaeological rescue of the style. Is important to notice that those drawings were made in the eve of the II Vatican Council and in a way they are charged with the expectations many young lay Catholics had about the maturing of an ecumenical perspective and a spiritualized perspective for daily life.

By the end of the fifties the spirit of renovation was felt in Latin America as well as in Catholic Europe. Fr. Gabriel Chávez de la Mora OSB, Ricardo De Robina, Matías Goeritz y Luis Barragán were architects of the time who built in a revolutionary fashion when approaching the temple. Mexico was a pioneer in the changes of religious Catholic art at the time. The remodeling of Cuernavaca Cathedral, the conception of a rounded chapel at the Benedictine monastery of St. Mary of the Resurrection in Ahuacatitlán, near Cuernavaca, the church of San Lorenzo and Santiago Tlatelolco, in downtown Mexico City and the chapel of the Clarisas Capuchinas of Tlalpan, are important examples of the new concept of spaces for worship, even to the point of adapting ancient XVIth century colonial buildings to the new liturgy.

At the midst of the XXth century, people wanted to access to a church not as the builders and passive witness of the mysteries performed there. Modern man wanted to be part of the community who was "the Church", the assembly, the community in which midst God's presence will dwell. The Gothic façade of Hanhausen receives the approaching crowd with that spirit. Is Sunday's midday Mass, floating in the glow of the Angelus hour.

Some years later in 1973 he painted his last "imaginary cathedral", in the purest Sumi-e style of Japanese art, with minute dabs of Prussian blue watercolor and vermillion accents added to highlight the dramatic effect. It is a late Gothic building that could be mid way between Strasbourg and Milan late Gothic cathedrals. The 1973 Cathedral is more matter than idea: the building is firmly rooted in the ground, as if it were growing from it as a rock or a mountain. Yet the building conveys an experience of movement and sound: at the upper right side a bunch of brush strokes seems to flee from the towers. A flight of doves, startled by the bells tolling, go to the slumbering city as living fragments of the building. He was fifty five years old when he painted this cathedral; he was no longer the romantic he had been. Now his approach towards architecture and life was more weighted and realistic.

Some years later in 1973 he painted his last "imaginary cathedral", in the purest Sumi-e style of Japanese art, with minute dabs of Prussian blue watercolor and vermillion accents added to highlight the dramatic effect. It is a late Gothic building that could be mid way between Strasbourg and Milan late Gothic cathedrals. The 1973 Cathedral is more matter than idea: the building is firmly rooted in the ground, as if it were growing from it as a rock or a mountain. Yet the building conveys an experience of movement and sound: at the upper right side a bunch of brush strokes seems to flee from the towers. A flight of doves, startled by the bells tolling, go to the slumbering city as living fragments of the building. He was fifty five years old when he painted this cathedral; he was no longer the romantic he had been. Now his approach towards architecture and life was more weighted and realistic. Fig. 4 José Hanhausen. Catedral. 1973. Watercolor over Fabriano paper. Col. M. Hanhausen, Mexico

Latter, in the decades of the eighties and nineties Hanhausen painted obsessively the silhouette of México City Metropolitan Cathedral. Manuel Tolsá´s facade was reinterpreted as an emblem of the city just as the two volcanoes that since XIXth century have identified the Valley. Yet the real cathedral, despite the perfection of being painstakingly colored with Windsor & Newton watercolor over Fabriano paper lacked completely the spiritual force of the imaginary cathedrals of 1959 and 1973.

May be poised the question whether these two sketches of the Imaginary Cathedrals are an example of Expressionist architecture. Compared to the ones presented by Arq. Julio Jiménez in "Espacio sacro y lenguaje arquitectónico expresionista"[6], it could be found some silhouette similarity with Antoni Gaudi and Finsterlin works analyzed in that article. But Hanhausen´s sketches belong to a different conceptual universe. They do not pretend the romantic ideal of fusing Nature and architecture, less separate the sacred building from the urban surroundings.

In Arq. Jiménez article, expressionist architecture casts herself out of the urban setting, seeking Nature. He sustains that the Christ centered approach to the Western concept of temple were forgotten in those examples. Hanhausen drawings are different because their subjects do not attempt to survive in the void of the spirit[7], but to be the earthly dwelling of the Heart of the World, according to the theology of Hans Urs von Baltasar[8]. The temple in Hanhausen´s drawings is conceived as a motor, as the source of life and meaning for the community who built it for worship. They have to be in the midst of the urban surroundings because they sanctify the city.

These spaces designed as illustrations for the poetic world his friend had created were never conceived to be built in the real world, yet they are not what is known as fantastic architecture. They were made to be visual spaces for the images born of the words of the poems. Making gestural drawing, modeling values with light and darkness, leaving them void of all decoration, making them strongly symbolic, their historical styles become at a time modern and eternal. In the spirit of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ those buildings exist as a place for modern man to experience -thru the community- that God has not abandoned His Creation. Juan Plazaola SJ described them as "buildings that sing the praise to the Lord" in the midst of the world.

The II Vatican Council was summoned and eventually came to an end. The Catholic Church took a different trend from what Hanhausen and many of his generation had hoped for. His own life underwent too many changes. He managed to survive emotionally his last years, living an epoch he cared little to understand. He felt modern man was headed to drown in the grossest of materialism. Regarding these drawings today the soul feels the disappointment of all unkempt promises and broken dreams. Yet they freeze time in a moment of hope.

Almost fifty years after these drawings were made, they still glow with the spirit of hope they were conceived in. They were made in a very joyous and significant moment of his own life, with a new meaning derived from the advent of times he felt as the dawn of a new era. There is something in them of the enlightened blindness of someone in love. Once he disregarded them as mere "fantasies" -those were his words to me- apparently unaware that if an idea finds its way into paper, it already exists in a corner of reality. Without pretending to do so, he had painted an instant of prophetic inspiration.

In the midst of the 1959 Gothic facade is a rose window, an empty mandala of pearly quality. That geometry -the opening image of this post- attracts the spectator, fixing his eyes into that point. There is a goal, a center of attraction that reminds of the circular Heaven gate painted by Hieronymus Bosch in the XVIth century, where a tunnel of light is the threshold to transcendence.

José Hanhausen died on December 22, 2005.

The transcendence withheld in the space of his "imaginary cathedrals" is no longer a mystery for him.

Fig. 5 Hieronymus Bosch. Ascent to Heaven ca.1500-1504 http://tacitva.splinder.com/archive/2004-10

Fig. 5 Hieronymus Bosch. Ascent to Heaven ca.1500-1504 http://tacitva.splinder.com/archive/2004-10 [1] Iván San Martín. "José Hanhausen: las bondades del funcionalismo" in Arquitectónica, N.4 año.2, México: 2003 Pp.69-86

[2] Margarita Hanhausen. Interview made to Arq. Ernesto Gómez Gallardo Argüelles Contreras, México City. Autumn 2004.

[3] Mt 18,20

[4] Fausto Ramírez. "Historia mínima del Modernismo en diez imágenes" in Esther Acevedo et al. Hacia otra historia del arte en México. De la estructuración colonial a la exigencia nacional (1780-1860). México: Conaculta, 2001. Pp. 99-136

[5] Cfr. Fausto Ramírez et al. El espejo simbolista: Europa y México 1870-1920. Catálogo de la Exposición. México: MUNAL-CONACULTA, 2004

[6] Julio Jesús Jiménez. "Espacio sacro y lenguaje arquitectónico expresionista" in Arquitectónica, N. 7, año 4, México: 2005. Pp.45-56

[7] Idem.

[8] Hans Urs von Baltasar. Le coeur du monde. Bruges, Belgique: Desclee de Brouwer, 1956.

Comments

Post a Comment